The Town That Looked Like a Wes Anderson Film, and Voted Far-Right

Görlitz should be thriving. It’s gorgeous, intact, and cheap. Instead, it’s eerily quiet, politically hard-right, and haemorrhaging young people. What went wrong?

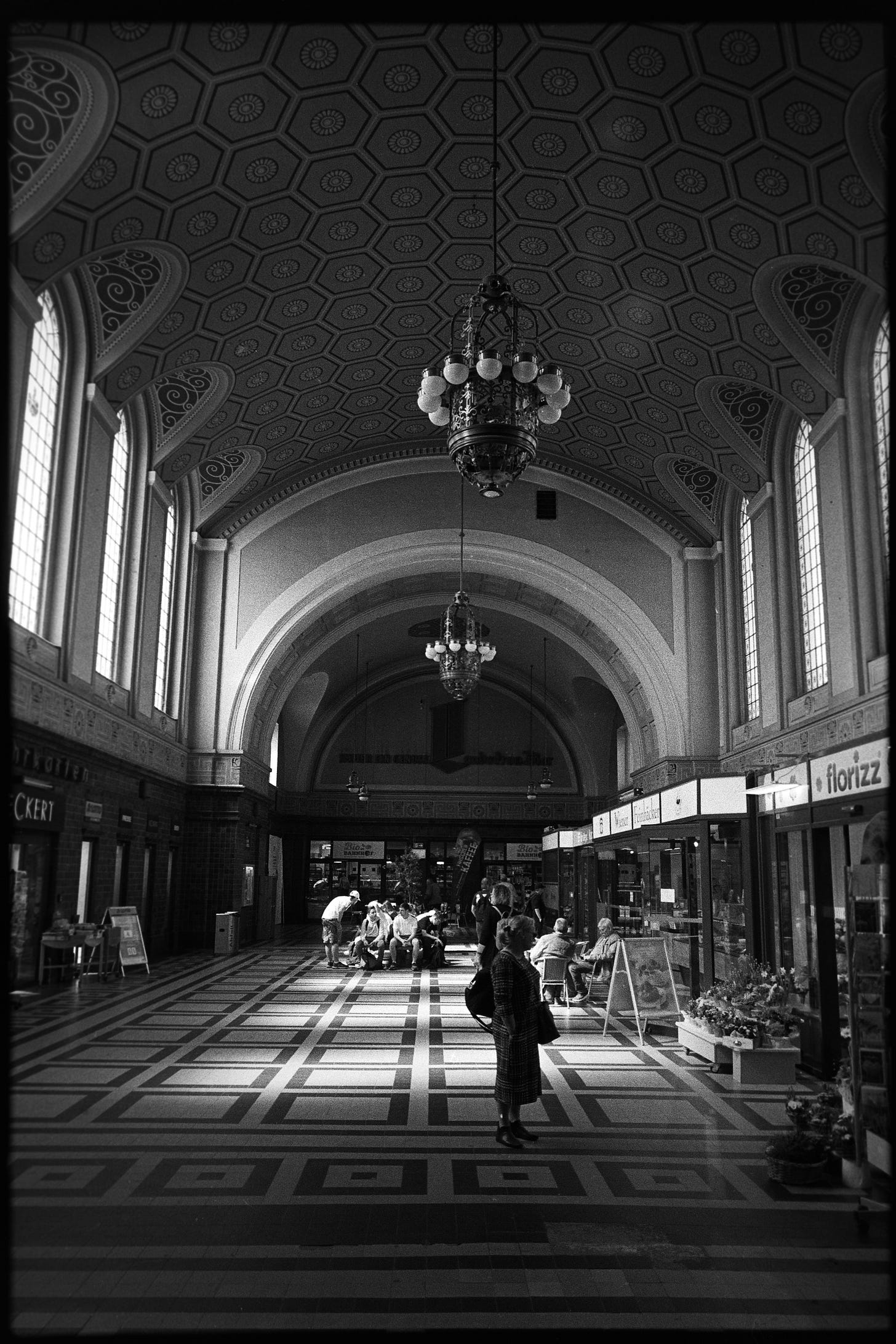

This is the third instalment of my photo project documenting the Germany-Poland border. Note: All photos taken with a Leica M6 plus 28mm Summicron and 50mm Summilux ASPH. I used Ilford HP5 Plus and developed and scanned the negatives at home. However, a couple of shots were using my Nikon Zf, too.

It took two and a half hours from Berlin and a quick change in Cottbus to reach the edge of nowhere. I boarded a lone diesel carriage that trundled south along the Germany–Poland border. With each stop, the world thinned out: deserted platforms, half-shuttered villages surrounded by Scots Pine forests, the eerieness of places that don’t register in our imagination. By the time I reached Görlitz, it felt less like arrival and more like time travel.

As the train pulled into the main station, my first thoughts were: this place is too beautiful to be this empty. The platform was haunting, chandelier-lit, and still. It felt like I’d stumbled into a Wes Anderson set no one had bothered to pack down.

I exited the station and wandered down Berliner Straße toward the centre. Görlitz is ridiculously beautiful for a town of 50,000, but it feels empty. Where is everyone? In the centre, many buildings have been lovingly restored (apparently by a wealthy American benefactor with ancestral ties to the city), yet storefronts remain boarded up and the streets eerily still. Since 1989, the city’s population has shrunk by 25 percent. To me, it felt like a desolate miniature of Prague.

About that “Wes Anderson vibe”. Several Hollywood productions, most notably The Grand Budapest Hotel and Inglourious Basterds, have taken advantage of this, using the city as a film set. The city has subsequently tried to rebrand itself as Görliwood with mixed success. For the former, Wes Anderson transformed the Görlitz Warenhaus, a grand early 20th-century department store, into the film’s surreal, pastel-toned namesake. It remains the city’s most famous screen moment.

Görlitz’s appeal as a film set is that it’s one of the few German towns that wasn’t flattened in World War II. It’s a well-preserved showcase of Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and Art Nouveau styles, like a living architecture museum that somehow dodged the bombs. Today, the city has among Germany’s lowest wages and one of the country’s highest shares of far-right voters. It sits tucked into an odd little corner at the far edge of Germany, pressed up against Poland and not far from Czechia. I knew I had to see it for myself.

Looking at the bridge ahead, I couldn’t help but think about how many flags this city has flown under. First documented in 1071 as a Slavic settlement, Görlitz passed through Bohemian, Saxon, and Prussian hands before becoming part of modern Germany. After WWII, the eastern half was carved off and handed to Poland; overnight, one city became two. German residents were expelled, Polish settlers moved in, and history split the town along a river narrower than a Berlin U-Bahn platform.

With this in mind, I crossed into Poland, and everything changed. Görlitz is postcard-perfect but feels frozen. Zgorzelec, just steps away, is scruffy, noisy, but more alive. The two sides of one city, split by war, politics, and a narrow river. Like Słubice, which sits opposite Frankfurt Oder, Zgorzelec is messier, its streets busier, with honking traffic and life.

The first thing you see are shops flogging cheaper cigarettes and booze and offering to swap your euros for Polish złoty. Many buildings look shabby compared to the German side, with crumbling facades and a few half-finished renovations. But money is coming in, and the gap is closing. Communist-era apartment blocks, forming a neighbourhood ironically named “Manhattan”, loom over the river on the Polish side, disrupting the fairytale city aesthetic. I stopped for some hazelnut and chocolate tart before walking along the riverfront.

Unlike Frankfurt Oder and Słubice, which feel like separate entities on either side of the Oder, Görlitz and Zgorzelec feel more tightly integrated. That might simply be because the Lusatian Neisse is far narrower than the Oder, and an international pedestrian bridge brings you straight into the heart of Görlitz’s medieval core.

As I walked around that medieval core, something in the stillness of the squares, the chipped pastel facades, and the late-afternoon quiet on a hot, midweek April day, 25 degrees and still as anything, made the place feel frozen. Like everyone had packed up one day and left the shutters open. I’m told Görlitz has a reputation for being a town of pensioners and a breeding ground for right-wing extremism. It felt melancholic, not sad exactly, but tinged. I couldn’t help but feel this is a city mourning its potential. Or waiting for someone to notice it’s still here.

And perhaps that’s the heartbreak of Görlitz. I got the sense of an outline of what it could have been. A cultural crossroads. A thriving river city straddling nations. A place where history didn’t stall out, where investment matched its architecture, where young people stayed instead of leaving for Berlin or Dresden. To its credit, the city and its Romanian-born mayor, Octavian Ursu, seem to be aware of this and have experimented with some novel ways to inject vitality into Görlitz. In 2019, the city began offering free one-month stays and studio space to creatives in exchange for feedback on what potential residents would want from a city.

As I walked back to the railway station, I imagined an alternate universe where this town is alive with artists, students, independent bookstores, a revived Polish-German tram clattering over the Neisse. I imagined its faded grandeur restored not just as heritage but as habitat. Cafés buzzing in old arcades, ateliers in former workshops, and weekend markets that blend Polish pierogi with Saxon wine. There were a few signs that perhaps the tide is turning. I noticed some boutique stores, but it’s hardly buzzing with artsy cafés and bars. I guess cheap rent and pretty streets only get you so far if there’s no scene, no momentum, no sense that something exciting is actually happening.

The creative class tends to follow momentum, and Görlitz doesn’t have it. And let’s be honest, like many towns in eastern Germany, Görlitz has struggled with xenophobia and far-right politics. The AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) has been strong here. In 2019, its candidate almost became mayor. That alone sent a pretty clear message to a lot of outsiders, especially migrants, artists, and left-leaning creatives: you might not be welcome here.

Görlitz is also simply too geographically isolated by German standards. It’s way out on the country’s eastern edge, closer to Wrocław than Berlin. Trains are infrequent, it’s not on any major high-speed rail lines, and getting there from Berlin involves a small diesel train that feels like it’s headed into the past. Psychologically, it feels cut off. The “preserved in amber” vibe is beautiful, but I got the sense it made the town feel suspended, as if time had passed it by. And while the border with Poland is right there, the connection to Zgorzelec doesn’t necessarily open it up in the way a dynamic border city might hope.

What I can take away from this is that Görlitz is beautiful proof that aesthetics alone don’t save a place. It takes will, vision, and a collective memory that doesn’t keep erasing itself. Unless something significant changes, it won’t become the city I imagined in an alternate universe anytime soon.

You’ve made it to the end!

If you enjoy this, consider recommending my Substack to a friend or leaving a comment. Normally, I post once a week, but I’ve been super busy, and this has messed with my schedule. Follow me on Instagram or Bluesky (if you’ve had enough of our tech overlords).

Another wonderful piece Ari with evocative photos and beautiful writing. It sounds like an intriguing place and that they are trying to make it better. I'd be fascinated to know what is behind the political angle - they are hardly overrun by outsiders so is it generated by fear or perhaps by a sense of having been left behind?

I like the sense of melancholy your writing evokes, while your photographs draw me in to feel I'm there walking the streets with you. Great journalism Ari.