Crossing the Oder: Germany, Poland, and a Tale of Two Europes

On one side, stagnation. On the other, scrappy ambition. What does this border tell us about modern Europe?

This is the second part of a series of photo essays on the Germany-Poland border (working title: B/Oderland ).

I don’t care for landmarks. I like the offbeat, grubby places in between. The ones that don’t fit cleanly on a map. The ones that belong to two worlds but never entirely to either. Borders, especially.

Living in Berlin, you’re constantly reminded of the scars left by a wall that split the city in two. But that’s been analysed to death. Instead, I’ve found myself drawn to a dreary brown river 80km east of the capital, the Oder, flowing from its mountainous source in the Czech Republic to the Baltic Sea. It marks a good chunk of the boundary between Germanic and Slavic Europe, between East and West. Along its course, towns sit awkwardly in the middle, straddling the line between Poland and Germany.

The closest one to Berlin is Frankfurt an der Oder (not the Frankfurt you’re thinking of), a small city of 57,000 on the border with Poland. On the other side of the river is the Polish town of Słubice (pronounced Swoo-bee-tseh), which, until 1945, was a district of Frankfurt known as Dammvorstadt. That all changed with the end of World War II when the victorious Allies redrew Germany’s eastern border along the Oder and Neisse rivers. On 2 July 1945, everything east of those rivers became part of Poland. By the end of the year, the town’s German population had been forcibly expelled and replaced with Poles, many of whom had been displaced from former eastern Polish territories annexed by the USSR.

These kinds of places fascinate me, so I decided I had to visit. I took the train from Berlin’s Ostkreuz station to Frankfurt – just 50 minutes away, but mentally much further.

Frankfurt an der Oder is a typical small East German city: austere yet functional and orderly. To its credit, it maintains a comprehensive public tram system, which is remarkable given its economic struggles (its population has shrunk from 87,000 in 1989 to 57,000 today). There’s no chance in hell that a city of this size in the UK, US, or Canada would have anything close to this level of public transit. At best, they’d have some infrequent buses, maybe a park-and-ride scheme. It goes to show what’s possible when transit is treated as a public good, not just a profit-making venture.

This is one of those things that makes life in Germany feel more civilised than in the Anglosphere. Even its drabbest corners function better than their counterparts in Britain or North America.

But that said, Frankfurt Oder isn’t an uplifting place. It’s shades of grey, with a few hues of Plattenbau pastel. There’s a quiet emptiness, a city that never fully recovered from post-reunification decline. Its wide streets, prefabricated buildings, and lack of real bustle give the sense that something’s slightly off. Despite being home to a university, this is a stagnant town of old people; the young and ambitious don’t seem to stick around.

But I was more interested in checking out Słubice on the Polish side of the Oder. Poland has made considerable strides in growing its economy over the last few years, but the contrast between how undeveloped Słubice feels compared to Frankfurt Oder is jarring. Słubice has the kind of border town energy you’d expect on the Mexico-US divide, somewhere like Nogales or Juarez, whose economies are tied up by the fact they are a stone’s throw from America. Of course, the difference is less extreme and certainly far less violent, but the average gross monthly salary in Germany is €4,925, while in Poland it is €1,381. This doesn’t account for Poland's lower cost of living, but the gap is still wide.

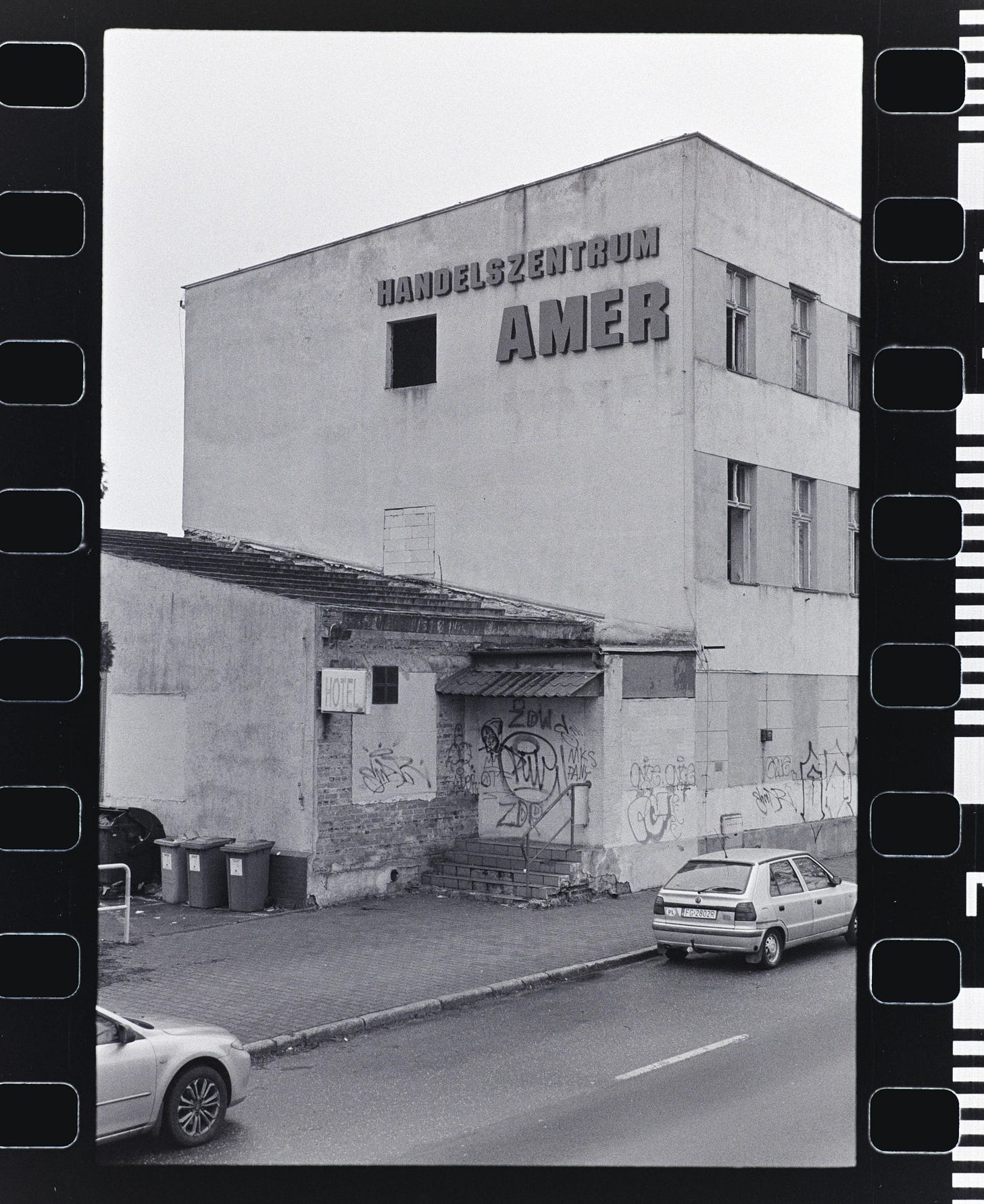

Crossing the bridge over the Oder from Germany into Poland, Frankfurt into Słubice, you’re hit with a mishmash of signage, utilitarian architecture, and the slightly chaotic arrangement of ads and storefronts; it all screams “scruffy border town.” In the 90s and early 2000s, Słubice was a frontier of the Wild East, a chaotic black-market hub; think counterfeit goods, untaxed cigarettes, illicit bars. It's more polished today, three decades later, but it still has a “border hustle” vibe. This is a town that exists to serve border-hopping daytrippers a slew of vices. Its economy runs on cigarettes, alcohol, fireworks, haircuts, and the likes.

But it’s interesting. Not in a way that makes me want to live here, but it’s fascinating how dramatically different it is from the East German town across the river. Whereas Frankfurt is sensory deprivation, Słubice is garish neon advertising, enormous billboards advertising cigarettes and fireworks, and empty land plots or abandoned buildings. The sidewalks are wonky, the layout haphazard, a patchwork of 19th-century Prussian townhouses, late-20th-century Plattenbaus, and the occasional modern glass-and-steel box. Right now, Poland seems more confident than ever about its future, while Germany seems less confident and full of doubt. You sense that with the rough and ready entrepreneurial hustle culture that is ready to seize opportunities on the eastern banks of the Oder. In contrast, the western banks paint a picture of a comfortable yet stagnant and risk-averse society.

The fact that the far-right nationalist AfD took 38.2% of the vote in last month’s federal election is shocking but unsurprising. Frankfurt (Oder) experienced a significant industrial decline following reunification, particularly in its semiconductor sector. The city’s largest employer, VEB Halbleiterwerk Frankfurt Oder, once East Germany’s leading semiconductor manufacturer with 8,000 employees, collapsed in the face of Western competition. By 2002, it was gone, along with much of the city’s prior economic relevance.

And yet, Frankfurt Oder isn’t some hopeless, post-industrial basket case. It has high-quality infrastructure that comparable towns in the UK, US, Canada, and even next-door Słubice could only dream of. The streets are clean, the trams run, and public services still function. The Viadrina European University keeps part of the city alive with students; there are seven German-Polish kindergartens. Around 10% of the population doesn’t have a German passport, which is high for this part of the country. On paper, this is ought to be a cross-border success story.

There was a cross-border tram that never happened. In the 2010s, serious talk was about extending a tram line across the Oder, better integrating the two towns for commuters, students, and shoppers. Słubice saw an opportunity; Frankfurt saw a threat. The idea that local taxes might help fund something that benefited the Polish side was enough to kill the plan. Never mind that Słubice residents cross the river daily to work and study. The fear was that a tram would simply make it easier for Germans to pop over for cheap cigarettes and booze, accelerating Frankfurt’s economic decline.

All the while, resentment simmers. The AfD knows this. The party is thriving in East Germany because people feel abandoned, angry, and protective of their own. Decades under the GDR shaped a different view of democracy and national identity. The AfD feeds off this. Populism plays a role, but the real fuel is nativism – a fear of foreigners and the belief in a Germany for Germans. Reunification promised prosperity but delivered mass unemployment, economic collapse, and a humiliating takeover by the West. Many Easterners think they are treated as second-class citizens, and left to stagnate while Western elites lecture them on democracy. The result is a deep-seated grudge, channelled into nationalism and anti-immigration politics. The AfD isn’t just a political party in the East. It feels like revenge.

After three hours wandering both towns, here’s my uninformed hot take: Słubice may be poorer on paper, but it’s making an effort. People hustle, even if that hustle mainly involves selling cheap cigarettes, fireworks and booze to those who travel from Germany. It’s rough around the edges, but at least it’s facing forward.

Frankfurt Oder has the ingredients of a functioning city. The tram runs, the streets are clean, and the services are satisfactory, but it feels like it’s waiting for someone else to fix it. Another way of putting this would be, while Słubice, across the river, asks, “What can we do with what we have?” Frankfurt Oder asks, “Who’s to blame for this?”

You’ve made it to the end

Congratulations. If you enjoy subjecting yourself to more of this, consider recommending my Substack to a friend or leaving a comment. Normally, I strive to post once a week, but last week was a bit of a whirlwind – work, family, travel, the whole lot – so this one’s a little late. I’m now in Portugal and hoping to have something interesting to write about my stay here later this week. Follow me on Instagram or Bluesky (if you’ve had enough of our tech overlords).

Love the photos and storytelling! Cool to hear about a place like this!

This project is so incredible, Ari. Your work always makes me feel as if I've actually been somewhere and learned something valuable. "Feels like revenge" is a pretty good summary of a lot of the political energy globally right now.