Monocle, TimeOut, and the Lisbonification of Everything

Some places are too marketable for their own good. Others are just fine.

I've just come back from a week in Portugal, having stayed in the entirely unremarkable town of Pombal, a place that exists between Porto and Lisbon not as a destination, but as a geographical fact. It has a castle, but no one comes here for leisure. No one ever will. It is not charming. It is not underrated. It simply exists.

I was here because my girlfriend's brother was visiting from Montreal with his Canadian-Portuguese fiancée, their kids, and his future mother-in-law to prepare for a wedding later this summer. I have no deep observations about Pombal, except that it has a Lidl and a train station, both of which have been useful.

Despite Pombal's status as a non-place in the imagination of tourists, it was a good base for exploring Porto, Lisbon, and Coimbra. Portugal's trains are cheap, functional, and operate on an unspoken agreement that punctuality is optional. Ten to fifteen minutes late is the norm here, just as it is in Germany.

March in Portugal isn't a golden-hour fantasy. It's wet, grey, and drizzly. Porto is a little less postcard-perfect when the Douro looks like a murky soup, but that has its own appeal. My girlfriend's priority was spending time with her nieces and nephew, but my aim was to go out and photograph.

I came equipped with a Leica M11 as my digital camera and a Leica M6 as my film camera. Naively, I packed three rolls of slide film: Kodak Ektachrome 100, Fujifilm Provia 100F, and Velvia 100. I hoped to capture colours like my mum did in her stunning 1990s slide film photography. Read my earlier Substack post for for the full story:

This conveniently ignored that I had been in Portugal exactly a year earlier and experienced a mix of overcast skies, full-on Atlantic storms, and occasional breaks in the clouds.

Alas, the weather didn't cooperate, and the slide film remained unused. Instead, I relied on five rolls of cheap and cheerful Kodak Gold 200, a film that does the job in bad weather, especially in Portugal's off-season.

I only spent a day in Lisbon, and the first few hours were a torrential downpour, so I retreated to a café and wrote my previous Substack post. Once the weather cooperated, I ventured out, making my way from Santa Apolónia railway station through Lisbon's tense tapestry of hillside streets, where vintage trams wove through, packed with tourists like a can of artisanal sardines.

This was my first time in Lisbon, and I barely spent enough time here to form a coherent opinion. All I have is an uninformed hot take – exactly what the internet doesn't need, but here it goes.

Lisbon is an incredibly beautiful, layered, and textured city. Its architecture, soft pastel hues fading and peeling from the Atlantic winds, and azulejos covering facades, stairwells, and metro stations, sits atop a landscape of steep hills and miradouros. It's a mix of neoclassical, Moorish, Manueline, and 20th-century Art Deco and modernism. There's nothing quite like it anywhere else in Europe. And then there's the light. Even though the weather was mostly shit, by late afternoon it cleared just enough for that soft, golden, almost cinematic glow that Lisbon does so well. No wonder everyone photographs this city.

And herein lies the problem. Lisbon is too beautiful, too unique, too perfectly located for its own good – and it's paying the price. Even in early March, ostensibly off-season for Southern Europe, I was one of tens of thousands of tourists squeezing onto its wafer-thin pavements.

The city has also become a well-publicised posterchild for digital nomads from both Europe and North America, lured by freelance and "digital nomad" visas for those earning over a certain threshold. The problem is that they earn far more than the Portuguese median salary, warping the local economy and pushing up rents to the point where lifelong Lisboetas can barely afford to stay in their own city.

But Lisbon also suffers from another related problem, which I've dubbed the "TimeOut-ification" of its urban environment. TimeOut is a publication that everyone knows but no one reads. The only time it enters the conversation is when it drops its annual "50 Coolest Neighbourhoods in the World" list, at which point, the selected neighbourhoods brace for impact.

Having worked in travel journalism as an editor, I've been complicit in turning places where people live into aspirational products. I know people like me are part of the problem. While TimeOut doesn't create gentrification, it supercharges it by spotlighting the latest "undiscovered" neighbourhood just before rent doubles and Airbnbs take over. More recently, TimeOut has had Mexico City and Guadalajara in their sights, and locals are not very pleased.

Instead of showing how locals actually live, TimeOut sells cities as lifestyle products, reducing them to a checklist of "must-visit" experiences for short-term visitors who will never experience the consequences of their own presence.

And where this reaches its apex is the TimeOut Market, an unholy bazaar of a city's hip eateries, neatly repackaged into bite-sized options in a sanitized, gentrified, shopping mall-style food court.

Lisbon was the first to suffer this fate, but the cancer has since metastasized. Now, Montreal, too, has its own glass-and-neon temple to curated authenticity.

Magazines like Tyler Brûlé's Monocle play an equally insidious role in flattening cities like Lisbon, Berlin, and Kyoto into aspirational lifestyle products with a uniform, globally palatable feel. While TimeOut fetishizes lists, Monocle fetishizes authenticity, but only the kind that fits its aesthetic; think azulejos meets mid-century modern, heritage façades masking high-end boutiques, third-wave coffee shops, and pastel tascas rebranded as "curated culinary experiences." This is soft-power conquest, flattening the world into something tasteful, frictionless, and palatable for the globally mobile, design-conscious, “culturally literate” professional.

None of this is to say I don't like Lisbon, I do. I just notice this same nonsense happening to cities all over the world. I can easily see why people instantly fall in love with this city; I think I would, too. I wish I knew what the solution was, but I don't. But I'm sure it starts with putting the needs of residents, especially those who've always lived here – before the demands of lifestyle magazines and foreign investors.

On to Porto. I made a couple of day trips, my second time in the city. Porto is further behind on the gentrification pipeline,but still very much on it. I've only ever experienced Porto in March, but based on my brief time here, I'm convinced this is a northern British city that is roleplaying as a southern European one. It is a place that has a sense of familiarity and melancholy that I grew up with. Its topography, with steep streets tumbling down to the Douro, reminds me of Newcastle upon Tyne, close to where I grew up. The river cuts through Porto much like the Tyne cuts through Newcastle, its sides linked by iconic bridges. But Porto’s Dom Luís I Bridge, a double-deck iron arch, is undeniably more dramatic than the Tyne Bridge. There is also a certain scruffiness that both cities share. Newcastle and Porto both feel gritty yet grand, shaped by industry and a sense of working-class resilience, with plenty of stately buildings standing side by side with crumbling facades.

Yet Porto also has shades of Edinburgh. First of all, both are choc-a-bloc with tourists, but Porto's steep hills and multi-level views over the Douro remind me of Edinburgh's Old Town rising above Princes Street. Both cities have an old, brooding character, especially in the rain. Porto's azulejos and granite buildings evoke a different aesthetic than Edinburgh's grey stone, but both cities carry a sense of history pressing in on you. I am no fan, but it is obvious J.K. Rowling absorbed elements of both cities into the Harry Potter universe. It has been covered to death elsewhere, so I will leave it at that. I'm also deeply impressed with the city's hybrid metro/light rail system.

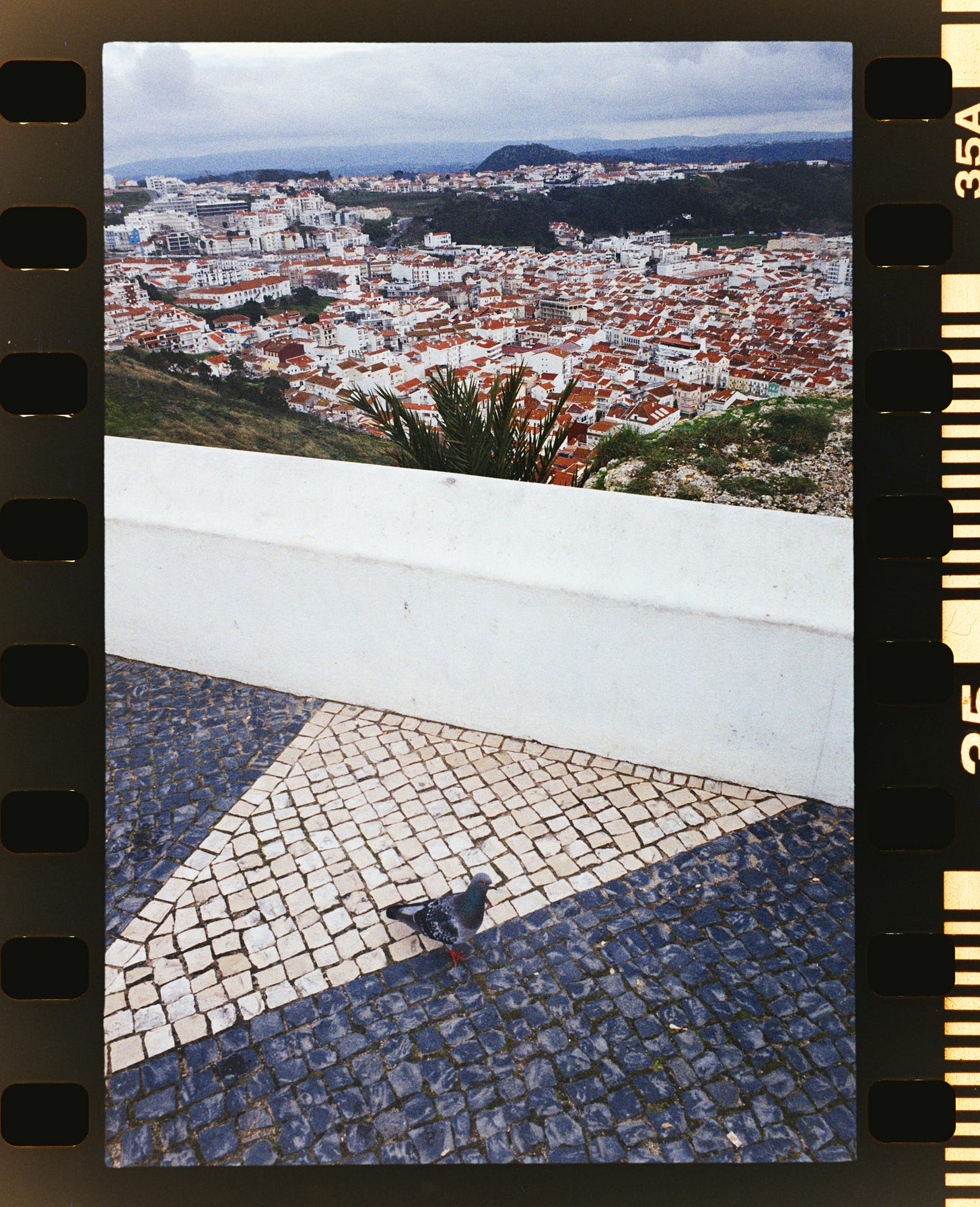

I also spent afternoons in Nazaré, a place that looks eminently photogenic, except when the Atlantic is dead calm. There were no waves, no dramatic skies, just a dry, overcast day with distinctly off-season vibes. Coimbra was different. It’s an incredibly charming small city, but beyond wandering its narrow hillside streets and checking out the university, I don't have much to add. I was barely there.

Which brings me back to Pombal. As I mentioned at the beginning, there's nothing fancy about this town, I'm certain not much has changed here over the years, but that's okay. To me, this is the Portugal that most people live. Somewhat plain, banal and everyday, and I mean this in a good way. Much like Carlisle in the north of England close to where I grew up. And that's just fine. One of the plus sides to places like this is that the locals will never have to worry about TimeOut or Monocle writing lists or fetishizing it. People can live their lives much as they did. And spending time here made me appreciate this other side of Portugal for what it is; unvarnished, unmarketed, and simply lived.

You’ve made it to the end

Congratulations. If you enjoy subjecting yourself to more of this, consider recommending my Substack to a friend or leaving a comment. Follow me on Instagram or Bluesky (if you’ve had enough of our tech overlords).

It’s impossible not to fall in love with photography by reading your articles! Thank you for spreading the passion!

Nicely done, Ari. I think you should have put "culturally literate" in scare quotes!

It's not just travel mags, to some extent, it is photography itself. One the one hand, the image serves as artifact of a specific time and place. On the other hand, by virtue of being photographed, this time/place is held up as special. And then there are copies. Soon, we are on our way to a marketplace in "the perfect _____." And besides, capitalism thrives on comparison . . .anyway, much more to say.