Inside the Vietnamese Megamarket Changing East Berlin

Long before reunification, Vietnamese workers were building East Germany. Now, their legacy lives on in the vast, chaotic maze of the Dong Xuan Centre – and it’s no longer just Vietnamese.

Migration stories in Europe usually follow a familiar script: arrivals in London, Paris, maybe Berlin – but rarely Lichtenberg. Yet long before reunification, a quiet current of Vietnamese life was flowing through East Germany. On the edges of East Berlin, you’ll find something unexpected: phở stalls, fabric shops, and the low murmur of a community that’s been here for decades. Once overlooked, it’s now impossible to ignore.

How did a Vietnamese community end up in East Germany? North Americans and Western Europeans (and I include myself) often view migration through a Western-centric lens, and we’re usually ignorant of the fact that people move across all corners of the globe, not just to Western nations. We naively and perhaps arrogantly assume the former Eastern Bloc was a cluster of homogenous, white ethnostates. This couldn't be further from the truth. East Germany, for example, was more diverse than I’d realised, home to Cubans, Angolans, Mozambicans, Chileans, Poles, Soviets, and Vietnamese – who arrived as guest workers, political exiles, or refugees.

Today, the Vietnamese community still exists and is perhaps the most visible minority on the streets of East Berlin. Vietnamese restaurants are everywhere, especially in the East. And in the city's deepest DDR-era urban tapestry, surrounded by brutalist tower blocks, you'll find Europe's largest Vietnamese wholesale market.

From 1978 onwards, the DDR signed contracts with socialist countries like Vietnam to recruit workers. By 1989, around 60,000 Vietnamese were employed at state-owned enterprises like VEB Elektrokohle Lichtenberg, which produced carbon brushes for industrial motors. It was supposed to be a win-win deal – East Germany got cheap labour to address production shortages, and Vietnam's communist government skimmed 12% off the wages to fund economic development projects. Think of it as socialism's answer to international staffing agencies.

Life for the Vietnamese workers, though, was tough. They were allowed to stay in East Germany for a maximum of four or five years, and socialising with DDR citizens outside of work was discouraged. Most were housed in cramped six-square-metre dormitories, and visa rules were strict: if they fell ill for a prolonged period, suffered a workplace accident, or got pregnant, they risked deportation back to Vietnam.

Everything changed after the Berlin Wall fell. Many of the 60,000 workers had already lost their jobs. They were forced out of their dormitories before East Germany was absorbed into the Federal Republic of Germany in 1990. As the DDR's state-owned enterprises were shut down or privatised, their contracts became worthless. But 16,000 remained.

Throughout the 1990s, they faced horrendous racist abuse and violent attacks by neo-Nazis. Without the right to work legally, many stayed afloat through self-employment – running nail salons, restaurants, or small shops. It wasn't until 1997, after seven years in limbo, that these former contract workers were finally granted permanent residence rights on humanitarian grounds.

One of those left in limbo was Nguyen Van Hien, a former contract worker at Baukombinat Ost, the massive state-run construction firm that built much of East Berlin's prefabricated Plattenbau housing. Like many others, he had to pivot to survive in the new capitalist order. He turned to importing and selling textiles, launching his first store for Asian goods in Leipzig. He named it Dong Xuan Centre in honour of Hanoi's Đồng Xuân Market – one of Vietnam's largest wholesale markets. In 2003, he bought a patch of industrial wasteland in Lichtenberg, where VEB Elektrokohle once stood. Two years later, the Berlin branch of Dong Xuan Centre opened its doors.

This wasn’t my first visit to Lichtenberg or the Dong Xuan Centre. I did a 12-hour photo walk through the neighbourhood last year and visited Dong Xuan in January 2023. But I was inspired to return after seeing Stefanie Bürkle’s Venice BeReal at the European Month of Photography – an exhibition exploring how Venice has become a global symbol, endlessly copied and reimagined. From fake canals in Las Vegas to German ice cream parlours, it showed how places are replicated through design, creating a feedback loop between the real and the imagined.

Bürkle’s earlier work was also on display, notably one about the Dong Xuan Centre in Berlin and Dogil Maeul in South Korea. The latter is a village built by South Korean guest workers in West Germany who were employed as nurses or miners during the 1960s and 70s before returning home. Rather than fully reintegrating into South Korean society, they used their savings and pension to build a little version of Germany, with Bavarian-style houses, bratwurst, and even a yearly Oktoberfest. It’s reverse migration, where people bring back not just money, but also an entire lifestyle, aesthetic, and cultural imprint from where they lived. I’d love to visit, but for now, Dong Xuan Centre, just 35 minutes away by S-Bahn and tram, was the more realistic option.

For the uninitiated, walking through Lichtenberg feels like stepping into an alternate vision of society, a remnant of a civilisation and a way of thinking that vanished overnight. A capitalist veneer has been placed on top, but the built environment still shapes how people think and feel, probably in the same way as it always has. Having spent a decade surrounded by car-centric North American suburban sprawl and moved to East Berlin two and a half years ago, I appreciate and understand more than ever how the built environment shapes daily life in ways ideology alone can’t erase.

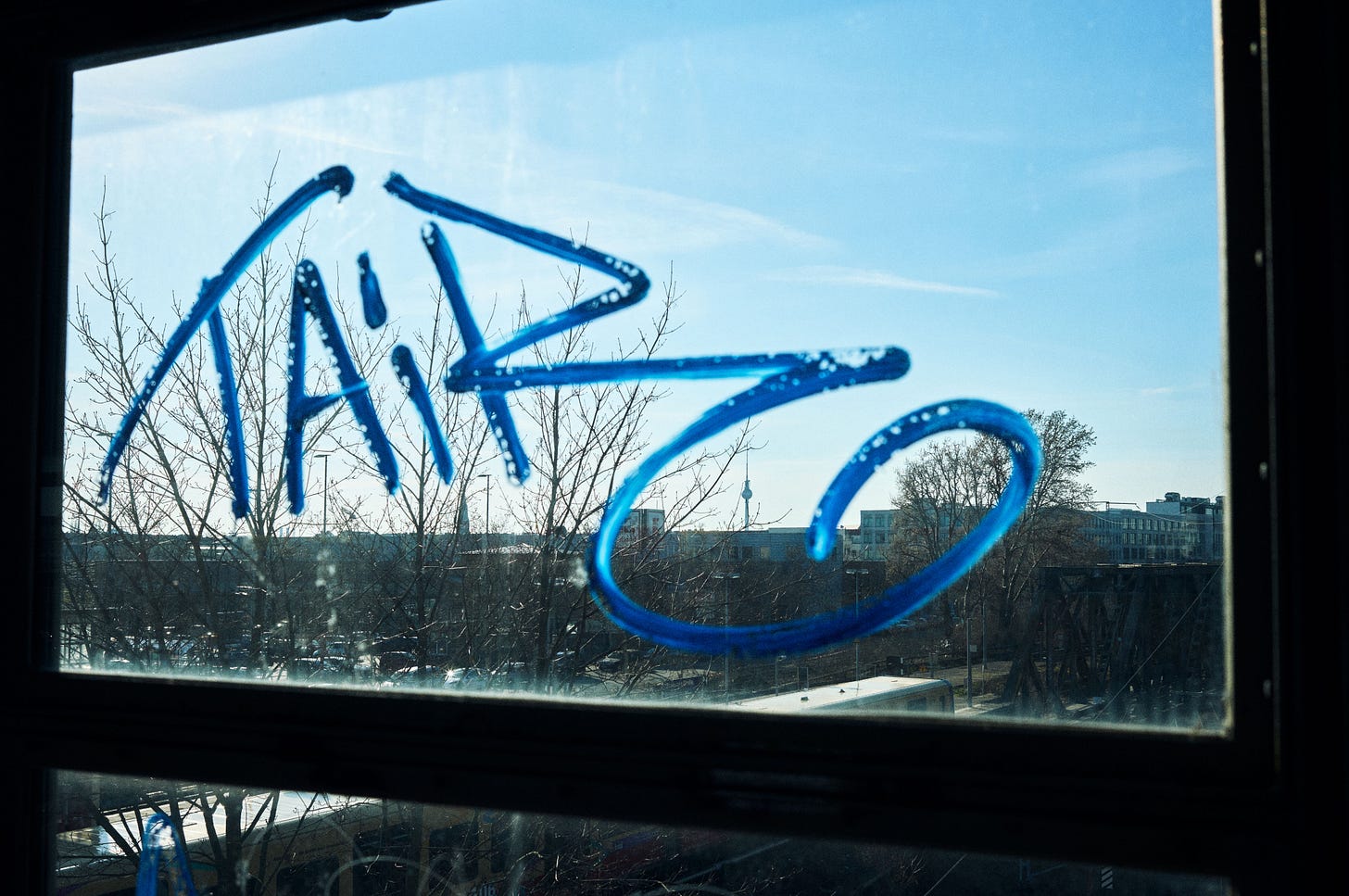

The Western narrative tells us these urban spaces were designed to crush individuality. Yet, many of them feel more liveable and thoughtfully structured than what capitalism has churned out. But what surprised me was how they seemed to foster a sense of community, peace, and quiet. Many contain vast inner courtyards, and the traffic noise is barely audible as cars are funnelled onto large boulevards. In many ways, they’re nowhere near as bleak as they’re often made out to be. Throughout Lichtenberg, there are hints of the neighbourhood’s Vietnamese character dotted around; speciality food stores, bars, murals on the sides of apartments, or just the people you’ll see wandering the streets.

While my borders project has focused on the imaginary lines between nations, I realised this place also fits. The Dong Xuan Centre was modelled after Hanoi’s Đồng Xuân Market, creating a little Vietnam in the heart of Lichtenberg – the most East Berlin of East Berlin districts. I was fascinated by the idea of a direct transplant of Vietnamese commerce, culture, and daily life into the DDR’s old concrete bones. Migration doesn’t just reshape places; it creates new ones. And those places, in turn, shape who we become. However, wandering around the market and taking photos for several hours, I stopped only once – for the best Indian biryani chicken I’ve had in Berlin. That’s when it hit me: there’s more to the story of the Dong Xuan Centre. It has become something more significant than just a Hanoi-to-East Berlin cultural transplant.

First, it’s hard to articulate just how enormous this market is. In raw numbers, it covers 165,000 square metres (around 1.78 million square feet) and consists of dozens of corrugated units. What’s striking, though, is how the Dong Xuan Centre has grown far beyond its Vietnamese roots. Walk through its warehouse-style sheds today, and you’re greeted with a dense patchwork of cultures beyond Vietnamese: Indian, Pakistani, Afghan, African, Arab, Central Asian, Eastern European, and so much more.

Sari shops sit beside tailors, spice wholesalers, and fabric merchants. Restaurants dish out everything from phở to biryani, while nail salons, barbers, and massage parlours are tucked between phone repair kiosks and hair extension stalls. You can buy LED lights, knock-off sneakers, or an ornately carved velvet sofa. I started to feel it’s more than a market; it’s a map of migration, integration, and resilience, charted through commerce, community, and the shared instinct to endure.

Places like Lichtenberg are often framed through a Western lens as symbols of post-socialist decay – unfashionable, ungentrified, and left behind. The Dong Xuan Centre sits quite literally on the ruins of the old East German economy, its halls built on the former site of VEB Elektrokohle. And yet, what’s emerged here tells a very different story. When you come from the global south, you’re not waiting for narratives of decline or renewal to be imposed on you. You’re just trying to survive, hustle, and carve out something of your own in the cracks of a wealthy country’s blind spots. It’s not about nostalgia. It’s not about ideology. It’s about building a life – and doing it on your own terms. The Dong Xuan Centre is what rises when forgotten people remake forgotten places.

A note about camera gear: All photos were shot on a Leica M11 paired with Summicron 28mm ASPH. If that means nothing to you, just know that it’s a very nice camera. Images were lightly edited using Capture One.

You’ve made it to the end

Congratulations. If you enjoy subjecting yourself to more of this, consider recommending my Substack to a friend or leaving a comment. This is part of a series of photo essays on borders, both between nations, but also between cultures and spaces. Let me know what you think, good or bad. Follow me on Instagram or Bluesky (if you’ve had enough of our tech overlords).

Marvilius!

Thanks for sharing this piece of life!

Till the age of 12 I was playing in those inner courtyards. Happy childhood and great memories. You captured it well!

Really interesting as always Ari, thanks for sharing.