Eisenhüttenstadt: East Germany’s Forgotten Utopia

A model socialist city that feels like The Truman Show directed by David Lynch

Borders are rarely as permanent as they seem. Today, the Oder River separates Germany and Poland, but not long ago, it was deep in German territory. Before that, it belonged to Slavic tribes. Before that? Who knows. I was tracing these invisible fault lines on Google Street View when I stumbled upon Eisenhüttenstadt, a city built from scratch as East Germany’s socialist utopia.

For centuries, German-speaking frontiers kept shifting eastward. Although Slavic tribes like the Sorbs, Obotrites, and Veleti lived in what is now Brandenburg, Saxony, and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern long before Germanic-speaking peoples arrived, the Ostsiedlung (eastward expansion) of the Middle Ages saw German settlers, merchants, and rulers push deep into what is now Poland, the Czech Republic, and the Baltic states, shaping cities like Königsberg (Kaliningrad), Breslau (Wrocław), and Danzig (Gdańsk).

Then came Prussia, the militarised state that would later unify Germany. By the 19th century, German influence stretched deep into Eastern Europe. However, the expansionism that built this influence also became its destruction. The two World Wars changed everything. After 1945, borders were redrawn, and 12-14 million Germans were expelled from lands they had lived in for generations.

So, back to Eisenhüttenstadt. This was a city born of a new postwar ideological and geopolitical reality. Its wide boulevards, strict urban planning based on neoclassical architecture, and idealised socialist realism murals immediately caught my attention. Even by the standards of East Germany, this was on another level of surreal. I knew I had to check it out.

A quick historical primer: The German Democratic Republic (GDR), established in 1949, followed the Soviet economic model, prioritising heavy industry as the foundation of its planned economy. The East needed its own industrial base, independent from the West. 1950 construction began on the Eisenhüttenkombinat Ost (Ironworks Combine East) near the Oder River.

But a steelworks alone wasn’t enough; the workers needed somewhere to live. So, the GDR built an entire city in the neoclassical style, originally named Stalinstadt. With the advent of de-Stalinisation in 1961, it was renamed Eisenhüttenstadt (Ironworks City), envisioned as a model socialist utopia, a showcase of the future.

First Impressions

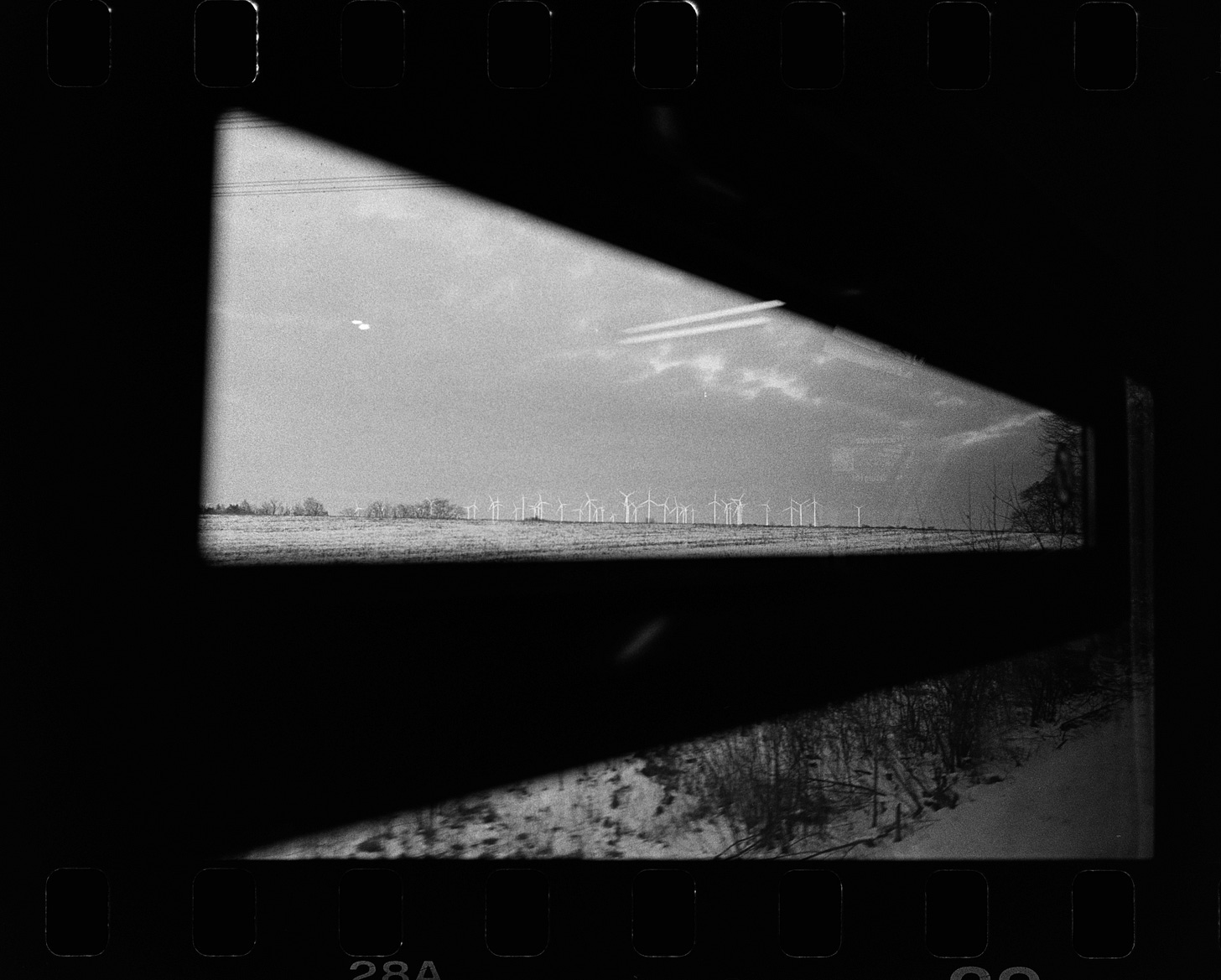

One of the best things about living in Germany is the Deutschland Ticket: for 58 euros a month, you can use the extensive public transport network, allowing you to travel freely across towns and cities without restrictions, except for high-speed rail. On a bright, chilly, snow-blanketed morning, I hopped on a train from Berlin's Ostkreuz station for the 90-minute ride southeast, changing at Frankfurt Oder before arriving in Eisenhüttenstadt.

The railway station is nestled in a sort of no-mans-land between the historical village of Fürstenberg on the banks of the Oder River to the east and a 30-minute walk into Eisenhüttenstadt to the west. Rather than wait for a bus into town, I decided to walk along the main road. The walk is oddly monotonous, a straight stroad (urban planning’s worst-case scenario, where a road tries to be a street and fails at both) flanked by suburban developments, car dealerships, and light industry, more reminiscent of North America than East Germany.

The first sign you're approaching the town is the massive sign saying 'City Center,' but rather than a geographical waypoint, it's the name of a sprawling strip mall complete with drive-through burger restaurants and chain stores, further adding to that odd American suburbia feel. Turn the other way, and the view shifts from capitalism to Marxism, a ten-story wall of socialist-era apartment blocks, effectively forming the city's boundary, not unlike the walls of a medieval town.

I came here to take photos but felt shy about walking around with my cameras out. Germans are inherently suspicious of cameras and more so in the former East. So, I wandered without a fixed route in mind. It turned out that no one really cared.

But one fact lingered in my mind: in last year’s European Parliamentary Elections, the far-right AfD took 36.5% of the vote here, with the left-wing but anti-immigrant Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht receiving 15.3%. This pattern isn’t unique to Eisenhüttenstadt, eastern Germany, outside of major urban centres like Berlin, Dresden, and Leipzig, has become fertile ground for populist movements. The reasons are complex but can be traced back to the region’s abrupt transition from a state-controlled economy to capitalism after reunification. As historian Katja Hoyer notes in Beyond the Wall, many in the former East struggled to adapt, fostering resentment and a lingering sense of being second-class citizens in unified Germany.

I was aware of this context as I walked through town. While I wasn’t expecting hostility, I did wonder how an outsider might be perceived. Yet Eisenhüttenstadt wasn’t as monochrome as the Ilford HP5 film loaded in my Leica M6. Ethnic minorities were going about their business, seemingly indifferent to the political undercurrents. A small AfD campaign event was taking place in the town centre, but it didn’t draw much attention. Given the town’s origins as a socialist model city, its political leanings today are less surprising than they reflect broader trends across eastern Germany.

The GDR seemed confident that an ideal society free of fascism could be built from the ground up, so long as the ground was arranged correctly. Eisenhüttenstadt was to be the proof of concept, a socialist city designed with the same precision and ideological commitment as a five-year plan. They assigned architect and planner Kurt Walter Leucht to bring it to life, using the GDR's new '16 Principles of Urban Planning' as guide, with the understanding that cities were not organic entities but systems to be structured, optimised, and, if necessary, entirely invented.

The result was a place where architecture didn’t just house people but instructed them. The city followed a strict hierarchy:

City → Residential District → Residential Complex → House Blocks

A clear and logical order, ensuring that everyone knew where they stood – both literally and ideologically. Each district contained the essentials: shops, schools, cultural centres, and childcare. It may sound oppressive, and perhaps it was, but the planning wasn’t entirely without merit. For example, one admirable goal was to create pedestrian-friendly residential areas, shielded from traffic on the principle that main roads should not interfere with the city’s unity, and I'd say they certainly succeeded in that aim. They rejected modernist Bauhaus-inspired "international style" (which was deemed dangerously "cosmopolitan and capitalist") in favour of historically influenced architecture with socialist symbolism before prioritising cheaper standardised prefabricated buildings (Plattenbau) for mass housing from 1955 onwards.

The GDR’s Levittown

Entering the city along Lindenallee, the main commercial thoroughfare, it's evident that Eisenhüttenstadt is different. There is no doubt that this is a time capsule. Think of it as the socialist version of The Truman Show. I like it here.

It's both ugly and oddly beautiful. I didn't think I'd ever describe the neoclassical Stalinist architectural style as majestic, but there, I said it. The pastel-coloured socialist housing blocks feel oddly inviting, perhaps even leisurely. There's a surprising warmth to the original core of Eisenhüttenstadt, which, dare I say, has an almost Mediterranean vibe. The apartment blocks feature huge inner green spaces akin to plazas and arches; the decorative elements combine to give it a sense of humanity and ambition that Brutalism mostly lacks.

Eisenhüttenstadt and 1950s American suburbia share an eerie, almost parallel-universe quality: two ideological extremes constructing near-identical utopian visions for their workers. Both were planned, idealised spaces built to engineer a particular way of life. In the U.S., you had Levittown and other suburban developments, which sold a vision of individual prosperity and nuclear family perfection. In the GDR, Eisenhüttenstadt was designed as the "ideal socialist city" meant to embody collective prosperity and class harmony.

Eisenhüttenstadt feels like the perfect setting for a David Lynch-style dreamscape transposed upon a socialist setting. It shares that sense of artificial perfection masking something uncanny beneath, like those found in Lynch's American dreamscapes. The same uneasy energy as the Blue Velvet's idealised 1950s suburban streets but transposed into an East German workers' town where reality flickers in and out.

Eisenhüttenstadt wasn't just a city; it was a declaration, a manifesto for a new socialist Germany built in concrete and steel. The dream was clear: a worker's paradise, rationally planned, architecturally grand, ideologically pure. But history has a way of making fools of visionaries. The Ironworks is still there, but it employs a fraction of the workers it did during the GDR. The socialist dream vanished, and something remains stranger – a ghost of a future that partially arrived before being pulled away permanently in 1990. Since then, the town's population has decreased by more than half, from a peak of 51,000 to 23,000 in 2020.

Walking through Eisenhüttenstadt feels like stepping inside a film set where the actors have long since left the set. While the uglier prefabricated housing blocks have been demolished as the town's population shrinks, the neoclassical centre has been preserved and even restored to make the urban environment feel unnatural, like a glitch in time. Having grown up in the UK and travelled extensively in the U.S., Eisenhuttenstadt doesn't feel like somewhere like Buffalo in Upstate New York or Middlesbrough in England. It doesn't seem to suffer from the same sense of visceral urban decay along with all its associated problems; this is a genteel decline; the city's dignity remains intact like a person in a well-staffed senior living facility, but its best years are behind it. Still, the urban scale is uncomfortably grand for a town this small, grand avenues built for rallies and parades now see little more than the occasional cyclist or pensioner walking their dog. The architecture reflects the ideological project; the reality is slower, quieter.

Maybe that's why it lingers in the mind. In a country where Berlin – the capital, just a 90-minute train ride away – moves fast, erases, rebuilds, and continually reinvents itself at dizzying speed, Eisenhüttenstadt neither evolves nor decays. It merely waits. A dream half-formed, a reality half-forgotten – somewhere between utopia and an epilogue.

A note about camera gear: All the black-and-white photos were shot on a Leica M6 with Ilford HP5 Plus and Kodak Tri-X 400. The colour ones? Leica M11. Lenses? Summicron 28mm ASPH and Summilux 50mm ASPH. If that means nothing to you, just know that they’re very nice cameras and they work.

You’ve made it to the end

Congratulations. If you enjoy subjecting yourself to more of this, consider recommending my Substack to a friend or leaving a comment. This is the first in what may or may not become a series of photo essays on the Germany-Poland border (working title: All Along the Oder—open to ridicule). Let me know what you think, good or bad. Follow me on Instagram or Bluesky (if you’ve had enough of our tech overlords).

Danke Ari, as usual, I love the lighting in all of these, and am so glad you shoot b & w with your « really nice cameras that work » ;-)

The history and your writing bring these shots to life. Looking forward to more visual lessons from you.

Thanks for the inspiration, can't wait to get Berlin in front of my camera this summer!

Love the “note about the gear part”